Formal verification is getting some traction in the world of blockchains. But what is formal verification, why is it relevant for blockchains, and how can we make good use of it? No matter whether you’re just dabbling with crypto or you’re a web3 native, there’s definitely something here for you.

But what is formal verification?

Simply put, formal verification is a set of techniques for proving facts about code, e.g., “function foo() needs at most fee x” Or “calling bar(Bob) makes Bob richer by y ETH”. Formally verified projects consist of:

A specification (a.k.a. spec): A relatively short definition of what the functionality should be in machine-readable language,

An implementation: Runnable, practical (and hopefully efficient) code that provides the functionality of the spec,

A proof: A piece of code that proves that the implementation realises the spec. (Some formal verification frameworks don’t need a proof.)

The developer has to choose a (trustworthy) formal verification framework (e.g., Isabelle/HOL, Lean, Agda, or PVS), write the spec, the implementation, and the proof, and make sure that the proof passes muster with the framework. Since it’s code, the spec should also be accompanied by an explanation in natural language in the form of, e.g., documentation, a blog post, or even an academic paper. Alternatively, the spec is co-designed by the developer and the intendend user(s), or even exclusively by the user(s).

You might now wonder “why go through all this effort? Isn’t the implementation enough of a pain to write already?” The whole point of a formally verified project is to empower users to be able to do the following: first, the curious user reads the spec (manually, but without too much effort, likely aided by the natural-language explanation) to make sure that it expresses all the critical properties that the functionality should provide. (S)he then feeds the spec, the implementation, and the proof into the framework, which automatically checks that the proof is correct. Given that (s)he trusts the framework, the user then is certain that the implementation fulfills the spec, without reading a single line of implementation or proof.

A developer writes the spec, the implementation, and the proof. A user (a) manually checks that the spec defines the required functionality, (b) automatically verifies that the implementation realises the spec by (i) feeding the two, together with the proof, to the formal verification framework and (ii) checking that the proof passes, and then (c) executes the implementation.

For example, consider an airplane manufacturer that wants to outsource the implementation of the autopilot logic. The manufacturer writes the spec (specifying important stuff like “the plane won’t crash under any conditions that permit flight”), chooses a formal verification framework and hires a contractor to write code that provably implements the spec. The contractor writes the implementation and the proof and the manufacturer runs the proof by the framework – if it passes, the implementation is acceptable. Formal verification is used to increase security and reliability in a number of industries, such as aerospace, robotics, and, of course, blockchains.

An allegory for formal verification

The CTO is sold, you’ll be using formal verification for the next project. You, a competent dev, know test-driven development, functional programming, and a whole host of languages of every flavour along with their libraries, so how should you think about this new shiny tool? Here’s the best allegory I could come up with.

You’re browsing for a cleaning spray at the grocery store and you decide to ask the attendant for help. He immediately lights up:

“We just got this new brand that kills 99.9% of bacteria.”

“Why the hype? Every brand claims the same nowadays.”

“Sure, but this one isn’t just a marketing claim. Come.”

He then proceeds to show me this peculiar bottle. It definitely looks overengineered. Sure enough, there’s the familiar claim “kills 99.9% of bacteria” on the sticker. The attendant then takes the bottle to the counter, puts it in this unfamiliar box, and presses a button. The box starts whirring. After a minute or so, its display lights up green with the message “Kills 99.9% of bacteria: Verified ✅”.

“This box didn’t come cheap, but it’s a marvel of technology. It reads the sticker of any product you put in for claims like the one on this bottle and then starts this elaborate back-and-forth with the package. And this is no ordinary package, no. It’s made by a special nanomaterial, custom made specifically for the formula of this liquid, that can prove beyond doubt that the liquid matches the claim on the sticker – please don’t ask me how.”

To drive his point home, he proceeds to pick up one of the usual cleaning sprays in a plastic bottle from the shelf, pops it in the box, and presses the button. The screen lights up red this time: “Kills 99.9% of bacteria: Not verified ❌”.

“Sure enough, the box is made by a different company to the one that makes the cleaning spray and there’s an industry standard that dictates the back-and-forth between the box and the package, so I trust that the result isn’t rigged. Out of curiosity, I even tried replacing the cleaning liquid in the nanobottle with water and, as expected, the box wasn’t fooled.”

Sounds like magic, right?

While technology is very far from such a feat for physical products[citation needed], this is essentially what formal verification does for software today. You’ve probably already gathered that the sticker is the spec, the nanobottle is the proof, the liquid is the implementation, and the box is the framework. And, contrary to the allegory, virtually all formal verification frameworks are free to use. They are also open-source – they wouldn’t be trustworthy otherwise.

How is formal verification in practice?

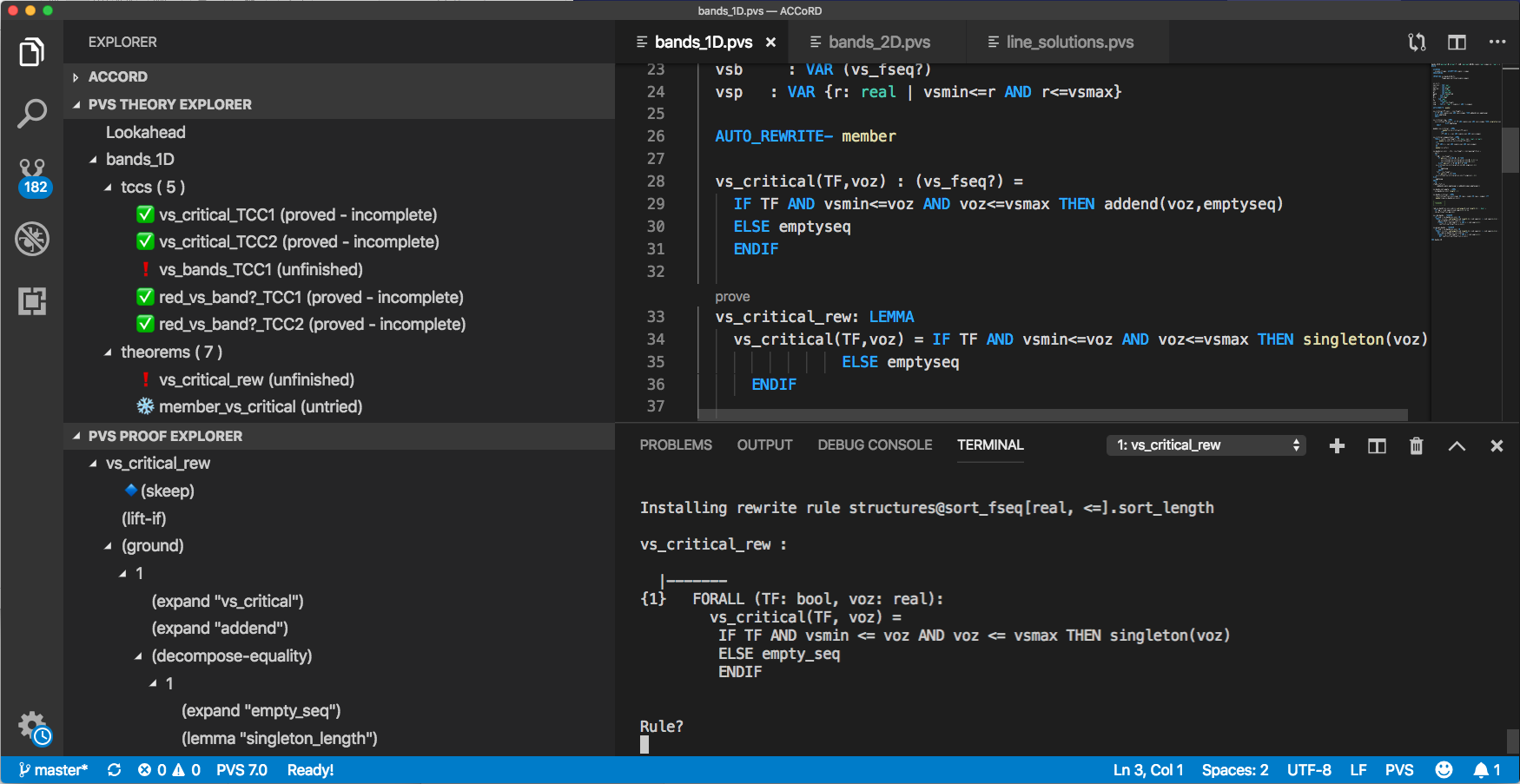

Allegories are nice and all, but how does formal verification actually look like? Most frameworks (that you should care about) integrate well with the usual suspects editors (VS Code, Vim, Emacs). The details largely depend on the framework, but in general there is an editor panel and an explorer panel. The editor is used to edit the spec, the implementation and the proof, while the proof explorer shows the progress towards proving the desired goals. Usual features such as “go to definition”, code completion, and hover hints are supported.

VSCode-PVS with the proof explorer on the left and the editor and terminal on the right.

This screenshot is taken from the formal verification environment PVS. Let’s take a moment to understand what’s going on here. The theory explorer contains a tree of proofs, in which each leaf is a “proof obligation”, i.e., a fact that needs to be proven. The proof obligations with a ✅ are already proven, whereas the rest are not. If all proof obligations are proven, then we’re done. Under the theory explorer we can see the proof explorer. This pane shows the actual steps that have been taken while trying to prove the vs_critical_rew lemma. These include steps such as expand, which replaces functions with their definitions. These steps are done semi-automatically.

The exact way in which these steps are taken vary wildly from framework to framework and different frameworks give different tradeoffs. Some, such as model checkers (e.g., TLA+) are fully automatic but they may fail to find a proof within a reasonable amount of time, especially if the goal is complicated, and then you’re out of luck. Older ones are too manual to be useful – we can all agree that manually expanding function definitions all the way to fully unrolled data types to prove anything is not the best use of our time, but should be done by machines. Modern ones (e.g., Lean) take advantage of powerful automation while allowing the developer to drop down to fully manual if desired.

A popular type of automation tools is SMT solvers such as Alt-Ergo and cvc5. These are tools that receive a logical formula parametrised with some variables and try out concrete values with a combination of brute force and heuristics until they can prove the formula or time out – they are somewhat like model checkers in this regard. In their most common use case, SMT solvers are integrated into an interactive formal verification framework and are used to prove relatively mundane and trivial low-level results, which the developer ties together manually into proofs of high-level facts. It is common to use an SMT solver (with the press of a button) to prove each leaf of the proof tree.

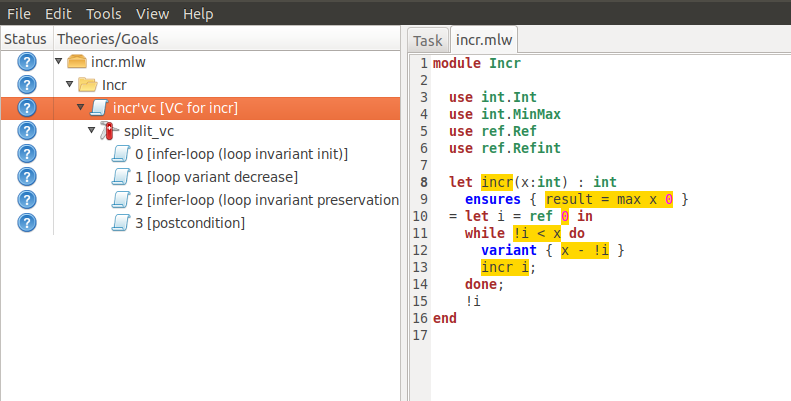

Why3 IDE showing how a post-condition and a loop variant are interspersed with implementation code to guide the automated prover.

The manual parts of the proof are usually provided as pre- and post-conditions that surround functions, as well as expect()-like requirements within the functions. Normally, such “annotations” are written in the specification language and are interspersed with the implementation language. In the screenshot above you can see how the Why3 framework uses an ensures block at the top of the function definition to encode a post-condition and a variant block within the function to aid the automated prover. Why3 has strived to keep the implementation and specification languages close to each other to flatten the learning curve.

VS Code with Agda mode: the editor on the left and the goal-and-context panel on the right, assisting interactive proof development.

The screenshot above is taken from Agda. Compared to other popular languages, it has less automation but a very strong type system that can prove lots of facts without leaning heavily on flaky approaches like SMT solvers. In its side pane, we can see the current goal that’s being proven, as well as a list of available facts. As you can see, Agda’s side pane is more geared towards proving individual goals, whereas Why3’s and PVS’s side panes give an overall view of all goals that are to be proven – this difference in interface reflects the differences in their underlying philosophy.

Apart from the level of automation, here are a couple more considerations that go into choosing a framework: Firstly, how close is the implementation language to executable code, or how easy it is to extract efficient executable code. Frameworks such as Dafny and F∗ are designed with executable program extraction in mind. Secondly but also very importantly, make sure that the framework you choose has great documentation and a large and friendly community, ideally using it for things similar to what you plan to do: If you want to prove that your smart contracts won’t lose your users’ money, don’t choose a framework that’s solely used in aerospace, except if you’re willing to take a not-so-short detour before starting to verify your smart contracts. To wrap up this tour of frameworks, I should also mention Isabelle and the venerable Rocq (formerly Coq).

Blockchain applications

There’s a conspicuous lack of the word “blockchain” up to now. We put this right in this part. Formal verification is suitable both for verifying high-level properties of smart contracts and of the blockchain infrastructure itself. For example, a substantial effort has been invested in formally proving that the Plutus Core language (the language used for smart contracts on the Cardano blockchain) and its semantics are correct. Furthermore, IOG is in the process of formally verifying that Ouroboros Praos, the core consensus protocol of Cardano, provides the two high-level security guarantees that all blockchain consensus protocols should provide, namely safety and liveness. They are using Agda entirely for this effort. Another consensus protocol that has been formally verified is that of Redbelly, this one using a model-checking approach.

Some Layer-2 protocols have also been formally verified. For example, the author of this blog post (c’est moi) has co-authored a formal verification effort of the Lightning Network using Why3.

Formal verification of Smart Contract properties

(Statistically) more relevant to you dear reader is the wealth of projects that provide tools for formally verifying your Ethereum smart contracts. I won’t go over all of them here, I’ll just mention a few prominent ones.

The most straightforward one to use is SMTChecker, which has the advantage of being integrated in the Solidity compiler. It allows you to pepper your code with assert() statements and flags any ones that don’t hold, in which case it also gives counterexamples. A useful trick is to write a public view function alongside your other Solidity functions that only contains assert() statements. The tool will then prove whether these “invariants” hold in between function calls. SMTChecker proves stuff fully automatically, so you don’t need to go out of your way to make use of it, but it won’t prove complicated things. These setup instructions worked for me (YMMV).

Halmos and hevm are two competing symbolic execution frameworks that are easy to use if you’re already familiar with Foundry, a prominent smart contract development environment, and its fuzzing capabilities. Symbolic testing is a formal verification approach that is a bit like your run-of-the-mill testing. The difference is that, instead of using concrete, representative values for variables when testing, or generating large numbers of semi-random values when fuzzing, symbolic testing tries to check that your assert()s hold for any possible value. Like model checking, symbolic testing doesn’t need a proof. Like model checking, it might run out of time and fail to prove all properties. The Foundry-friendly symbolic execution approach is taken a step further by Kontrol, which also allows you to manually help guide the automatic prover by writing intermediate lemmas. Like SMTChecker and differently to the high-level exposition above, these approaches allow you to mix the spec and the implementation.

Certora is another smart contract formal verification tool that takes the automatic proof approach. More in keeping to our high-level division of spec and implementation though, it provides a specialised language for writing your spec, CVL. It was initially closed-source, but was open-sourced in February 2025.

VerX is a closed-source tool that allows you to describe complex properties of your smart contract. The specification is written in a separate file, which uses a few special “temporal” keywords such as always(), prev(), and once(), as well as the usual logical connectives such as && and ==> (implication). More details can be found here. You cannot run it locally but have to submit your code using their API, probably so that they can keep the source closed. In my opinion, keeping the source of security-critical software closed drastically reduces its trustworthiness.

I shouldn’t fail to mention Clear, the formal verification framework for the Yul intermediate representation language, as well as the Move Prover which is tightly integrated with the Move smart contract programming language.

Formal verification of blockchain infrastructure

But maybe you’re the exception and you’re considering taking up the ambitious task of rolling out some new formally verified infrastructure, e.g., a new consensus engine or layer-2 solution. In that case, you’re admittedly much more on your own – you won’t find a wealth of blockhain-infrastructure-specific formal verification projects out there. The main difference is that you would presumably want to use an efficient programming language for bare-metal software such as Rust or Go (or C/C++ if you’re old-school), not Solidity.

One approach here is to write your code in such a language of your choice (I recommend Rust for the sake of your sanity), and then use one of the many available tools: the model checker Kani, the experimental Verus, or the somewhat more mature Aeneas and Creusot. Apart from Kani, at a high level, their approach is this: they provide you with ways to annotate your Rust code with pre- and post-conditions, they then translate your Rust into a formal-verification-friendly language such as Lean and lastly try to automate the proof as much as possible. Don’t be fooled though, for anything remotely complex you’ll probably have to manually help the prover (or try your luck with LLMs). For translating Rust to F∗, you can also use Hax, while for translating Rust to Rocq there’s also coq-of-rust. If you’re a fan of C, you can use VST. There are also a couple of closed-source solutions for C/C++: Escher C/C++ Verifier and Polyspace Code Prover, the second even provides certification for a few standards, namely EC 61508, ISO 26262, and DO-178. I wasn’t able to find a non-experimental tool for formally verifying Go.

This approach has the advantage that you’re mostly writing your normal programming language. It has the drawback that the automatically derived spec and implementation in the formal verification language is more complex, so any help to the prover will likely be quite arcane. The other drawback is that many of these tools restrict your use of standard features of the language. For example, Aeneas doesn’t support Rust closures.

There’s also the opposite approach: Write your spec, implementation, and proof directly in a language geared toward formal verification and translate that to a more standard programming language, which you can in turn compile to machine code. I’d recommend F∗ which compiles to OCaml, or Dafny which compiles to C#, Java, JavaScript, Go and Python. This approach ensures that you’re using a toolchain that’s been designed from scratch with formal verification in mind. It has a couple of drawbacks though: Firstly, you do need to learn these somewhat complicated languages. Even after if you master the new language, the main drawback then is that the resulting executables will most likely be less performant than those compiled from highly efficient languages like Rust. And, of course, don’t even think about tweaking the output code of F∗ or Dafny, otherwise you instantly lose all formal guarantees that you’ve tried so hard to get!

Honourable mentions

There are various tools that scan your EVM smart contracts for common vulnerabilities. A prominent example is Mythril. Such tools are only designed to find a fixed set of vulnerabilities and are not suitable for proving custom, application-specific properties, so they are not classified as formal verification tools (at least in my mental model).

Just the effort of writing a formal, executable specification of a language (a.k.a. semantics), without formally verifying that any specific compiler implements it, is substantial and important work. Such an example is KEVM, the formalisation of EVM, the bytecode language in which Ethereum smart contracts are stored and executed on-chain. To the best of my knowledge, no compiler to date provably implements the KEVM semantics.

Integration with existing systems

If you’re not starting a new project, but are trying to integrate formal verification into an existing one, well, that would be a bit more difficult in my opinion. First of all, you should be lucky enough to have chosen a language with some degree of formal verification ecosystem around it. Secondly, as we’ve seen, many formal verification frameworks don’t support important features of your language, so you’ll have to heavily refactor.

If this is your case, my recommendation is to start small and grow from there. Pick a simple part of your codebase and try to formally verify that first. This will force you to modify your toolchain to accommodate for the new tools and get a taste of the kinds of changes you’ll need to make to your codebase. You can then expand from there. I recommend that you have some ambitious, but realistic end-goal in mind and gradually work towards that. Proving the safety and liveness of your core consensus engine in the face of Byzantine corruptions is a good example of aspirational goal – aiming to formally prove the correctness of every single interaction of your user with the client frontend is probably overkill.

I am fully aware that you’re very likely operating in a competitive environment, so moving fast at first is crucial – I don’t blame you for not formally verifying your entire codebase from day one. If your consensus engine safeguards (hundreds of) millions of dollars though, you should probably start considering it, even though now you’d wish you’ve started off with formal verification in mind already. That’s a textbook case of a catch-22 if there is any.

These are some hard tradeoffs. Anything easier?

I won’t pretend that formal verification is your run-of-the-mill development. You’ll need a bigger engineering effort, higher expertise, and longer timelines than usual. Does that mean that you should just give up and write blazing-fast but totally unsafe C, put together a demo that seems to work and call it production-ready? Definitely not! The usual software development recommendations can still go a long way towards better software:

Use a strongly-typed language (and actually make use of the types!) to rule out entire classes of bugs – some go as far as putting Haskell in production, although in my opinion Rust is pretty much always the way to go (yes I’m a fanboy 🦀).

Do property testing, which essentially is a poor (wo)man’s formal verification: you specify properties that your code should have and the property testing framework tests your implementation on a large number of intelligently chosen inputs that could make your code violate your properties – it then shows you the offending inputs if any, otherwise it gives you some level of assurance that your code behaves as it should.

If you’re doing low-level stuff (e.g., bit manipulations, low-level network code, pointer shenanigans) (which you honestly shouldn’t be doing if you’re implementing a blockchain, there are libraries for that), also do fuzz testing. This throws random inputs to your code, trying to make it crash. It doesn’t test for arbitrary properties, but is better at averting disaster than property testing.

I’ve formally verified my code. Is it finally time to rest on my laurels?

No, not really. The ultimate goal is for your users to be able to read your spec, press a button, and run on their machine code that they can be sure implements the spec. That level of automated assurance isn’t really possible today. Let’s for a minute take stock of what level of support this would need: The operating system would have to somehow integrate trusted formal verification frameworks (independently from your code), download your source code, formally verify it against the spec, compile it with a trusted compiler, install it, and give your users the coveted “Spec verified ✅”. It took the industry several decades to make cross-platform software a reality, there’s no reason to believe that integrating formal verification would happen overnight. Even if this worked, the whole procedure would be quite slow, as verifying formal proofs and compiling large codebases isn’t instant. And slow = bad for UX. This is why most software managers just download and install pre-compiled executables, which of course the users can’t really verify at all.

In practice, the best you can do today to mitigate this glaring loophole is reproducible builds: Essentially, you publish your compilation pipeline and fix any possible source of randomness, so that a power user can follow your instructions, compile from source, and check that the executable (s)he built is exactly the same with the one distributed by their software manager. Most users will just use the pre-built executable, but a power user that chooses to compile from source can theoretically call you out publicly if the executable they build doesn’t match the one they can get from the software manager.

Also, who knows whether the users’ processors should be trusted not to send their secret keys to its manufacturer? After all, processors are almost exclusively closed-source and use opaque designs. More and more people are actually taking this issue seriously.

Another issue is that any useful codebase relies on libraries, which most probably don’t provide formally verified properties. This is an obvious weak point. I specifically mention here cryptographic libraries, which arguably warrant formal verification more than other libraries. In fact, there are some tools specifically for formally verifying cryptographic implementations mainly following game-based cryptographic paradigm, such as Tamarin, ProVerif, EasyCrypt, and CryptoVerif. I won’t give you a deep dive on these, this post is already getting too long.

Conclusion & Outlook

Phew, that was quite a ride! To sum up, we’ve seen what formal verification is, how it works in practice, discussed relevant tools, and saw existing limitations and tradeoffs. Bottom line is that there can be no scalable, practical, provably robust security without formal verification. Still, the field has a long way to go. Currently it is very hard to get efficient formally verified code without investing immense engineering effort. It is also hard to integrate formal verification with existing codebases. Choosing your battles, i.e., which parts of your codebase to formally verify, is crucial. Still, this is a quickly evolving area, so watch this space and beat the curve! I wish you good luck in your explorations! You might find this list of formal verification tools useful.