Sei Giga will be the new exciting era for the Sei blockchain system.1 Sei Giga will mark a major shift in how transactions are published, processed, and finalized in Sei. For this reason, Sei Labs commissioned Common Prefix to review the Sei Giga proposal and outline its findings in a series of blog posts.

In this second instalment we will explore the performance enhancements of Sei Giga.

Decoupling of transaction ordering and execution

In the first part, we discussed how Autobahn disentangles data dissemination from reaching consensus. This enables transaction and data dissemination to progress at the pace of the network, without being affected by consensus-related performance degradations, such as faulty leaders.

Sei Giga takes this idea one step further by decoupling the ordering of transactions from their execution. Specifically, in Sei Giga the organization of transactions in a ledger and their execution takes place via distinct operations that can be executed in parallel for maximum efficiency.

First, transaction data is disseminated across peers as discussed in Autobahn. Remember that, as long as a validator knows that the data is available somewhere, that is in some honest peer, they do not block their consensus participation until receiving this data. This enables lower latency and, using Autobahn’s parallel chain structure, higher throughput.

Following, transactions are organized in batches (blocks) and finalized via a Byzantine Fault Tolerant (BFT) consensus mechanism, which is executed among all participating nodes (validators). The output of the consensus protocol is a ledger of transactions organized in blocks.

After blocks are created, each validator executes asynchronously the transactions published in the ledger. The execution of transactions produces the updated global state of the system, which includes updated account balances and smart contracts’ internal state. Finally, a succinct commitment of the newly-computed state is published on-chain and finalized at a future block, when at least ⅔ of validators verify it and vote in support of it.

Interestingly, these operations are mostly independent and highly parallelizable. For example, new transactions are produced, organized in blocks, and finalized, while old transactions are being executed. Similarly, state commitment proceeds in parallel with block production and the publishing of new transactions, with blocks getting produced and transactions getting published in them, whilst validators execute older transactions and update the system’s global state.

Nonetheless, this parallelization effort and the asynchronous nature of the system comes with tradeoffs. Specifically, the finalized ledger of transactions is “dirty”, in the sense that a transaction included in a finalized block may be invalid, e.g., double spend assets. The idea of dirty (also called “lazy”) ledgers is not new and has been extensively explored in both the academic literature2 and deployed systems3. The main idea behind lazy ledgers is that, instead of invalidating an entire block when it contains an invalid transaction, the ledger is sanitized and invalid transactions are ignored when computing the new state.

One major consideration in lazy ledgers is protection against spamming. Because transactions are finalized in blocks before getting executed, an attacker could try to flood the network with invalid transactions. If no precaution is taken, then the blocks could be filled with these invalid transactions, thus delaying or altogether prohibiting the finalization of correct transactions. Note that it is impossible for a node to deduce whether a transaction is invalid without executing it,4 so a pre-emptive blocking of such transactions without executing them is not viable.

The common approach to prevent such spamming is enforcing the payment of fees for not-yet-executed transactions. In this way, every transaction incurs fees to its creator, regardless if it is valid or not, and, crucially, the calculation of these fees and their charging happens before the transaction’s execution and upon publishing it in a block. This means that the system needs to maintain some minimal state, related to the handling and payment of these anti-spamming fees, which needs to be updated synchronously with respect to the consensus mechanism. In Sei Giga, the details of such an anti-spamming mechanism are not yet known, but it should be expected that they are part of the overarching transaction fee mechanism.

Parallel transaction execution

Another point of performance exploration in Sei Giga concerns the parallelization of transaction execution. In the previous section, we discussed how transactions are executed independently from the consensus mechanism, that is after they are finalized. However, transaction execution itself can be further parallelized and yield better performance.

In the most straightforward manner, used in traditional blockchain systems, the ledger’s transactions are executed sequentially. This mode ensures that transactions are executed as intended and the final computed state is correct and consistent across all nodes, since everyone agrees on transaction ordering via the consensus mechanism. This is particularly important if two or more transactions are dependent, that is they access the same state elements. For example, if Alice sends to Bob 5 tokens (transaction 1) and then Bob sends 4 of them Charlie (transaction 2), then the correctness of transaction 2 is dependent on the existence of transaction 1; in other words, these two transactions need to be executed sequentially in order to compute the correct final balance changes (Alice -5, Bob +1, Charlie +4).

In Sei Giga though, transactions are executed in parallel. The core intuition behind this choice is that most transactions are not dependent on others, meaning they don’t access the same state elements. For example, if Alice sends to Bob 5 tokens (transaction 1) and then Charlie sends to David 3 tokens (transaction 2), these two transactions are completely independent and can be optimistically executed in parallel. When, however, two transactions do indeed access the same state, then such dependency is identified and handled appropriately, by rolling them back and executing them sequentially afterwards.

This mechanism is called Optimistic Concurrency Control (OCC) and has the potential to boost performance significantly, as demonstrated both in the literature and in practice.5 Note that OCC does introduce a tradeoff, since the dependent transactions add the overhead of roll back and re-execution. Therefore, OCC is particularly effective if most transactions are parallelizable, whereas it may degrade performance if the majority of transactions access the same state. Interestingly, some reports measured 64.85% of Ethereum transactions as being parallelizable,6 while others increase this figure to 83% on average.7 Therefore, if transaction parallelization in Sei Giga has a similar rate as in Ethereum, then OCC can significantly boost its performance compared to sequential transaction execution.

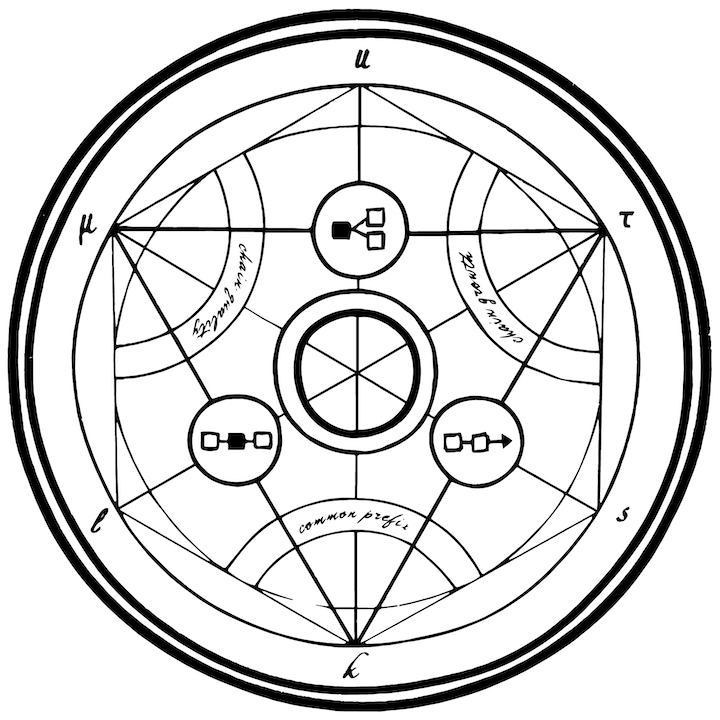

Data structures and primitives

A third approach that Sei Giga takes for improving performance is using non-standard data structures and cryptographic primitives, which are tailored to its particular needs. In this review we will not go into depth in Sei Giga’s implementation, but rather discuss three such components.

The first primitive is Log Structured Merge (LSM) trees.8 LSM trees were invented almost 30 years ago and are attractive for databases or file systems with high insert volume. In particular, LSM trees maintain data in two or more separate structures. Each data structure is stored on a different medium and optimized for it, such as RAM or SSD storage, with data synchronized across them efficiently in batches. In Sei Giga, LSMs are used to organize transactions in a block. In blockchain systems, the most common approach in organizing a block’s transactions is via Merkle trees,9 where each of the tree’s leaves contains a single transaction. Although Merkle trees enable secure verification of the contents of large data structures, they require traversing multiple tree nodes and performing repeated hashing operations when writing data. Instead, LSM trees are useful for storing key-value pairs and efficiently updating them in a parallelizable manner.

Following LSMs, Sei Giga also borrows ideas from traditional database and storage management by using a tiered approach for caching and storing data. Specifically, recent blocks and transactions, as well as frequently accessed state elements, are stored in memory or high performance SSDs. Instead, stale state or historical transactions are stored to cost-effective archival storage, such as a distributed columnar database.

Finally, Sei Giga uses a cryptographic accumulator10 in order to store the global state. As discussed above, after a block is finalized, its transactions are executed in parallel. The updated state, which results from these transactions’ execution, is stored in an accumulator in the form of key-value pairs. Accumulators are particularly tailored for Sei Giga’s use case for various reasons. First, they enable constant time operations, which is particularly important for processing large amounts of transactions. Second, they allow compact aggregation of membership proofs, across many keys in the structure. This is particularly useful for blockchain systems, where updates occur in batches (blocks), since it allows validators to update the state without performing multiple operations for each individual transaction, as is the case with re-hashing operations in Merkle trees. Third, the accumulator can be updated asynchronously, which is particularly fitted for Sei Giga’s parallelized transaction execution.

Conclusion

In this article we explored various approaches that Sei Giga takes in order to improve performance. We investigated the decoupling of transaction ordering from execution, which results in a lazy ledger. This approach is common in the literature, but needs careful consideration and implementation to properly sanitize the final ledger and avoid hazards like Denial-of-Service via spamming of invalid transactions. Next we discussed the parallelization of transaction execution. Transactions are assumed to be independent from one another and are optimistically executed in parallel. Nonetheless, when conflicts occur, for example if two transactions access the same objects of the global state, then the implementation should carefully roll them back and re-execute them in sequence, ensuring that the final computed state is correct and consistent across all nodes. Finally, we reviewed Sei Giga’s usage of non-standard data structures and cryptographic primitives for improving efficiency in various operations. These include LSM trees for transaction organization within a block, tiered caching and data storage, and cryptographic accumulators for storing the global state.

Altogether these approaches have the potential to qualitatively improve Sei Giga’s performance and enhance the guarantees achieved by Autobahn.11 Nonetheless, although they have been previously discussed in the literature and tested in some real-world systems, they need to be carefully designed, implemented, and reviewed, in order to ensure that potential corner cases are properly handled and hazards are avoided.

- https://www.sei.io

- https://arxiv.org/abs/1905.09274; https://arxiv.org/abs/1810.08092; https://eprint.iacr.org/2018/1119

- https://celestia.org

- This is a result of the infamous halting problem in computability theory.

- OCC has been explored in protocols like FastPay (https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.11506) and the more recent Sui Lutris (https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.18042), which is the core component of Sui’s distributed ledger (https://sui.io).

- https://blog.sei.io/research-64-85-of-ethereum-transactions-can-be-parallelized

- https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.05358

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Log-structured_merge-tree

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merkle_tree

- https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007⁄978-3-030-95312-6_17

- See Part 1 of our review.