Picture this: on a quiet Sunday morning, Alice is excited to swap a few ETH for a hot new token on a decentralized exchange. She submits her transaction and leans back, coffee in hand. Her request goes into the mempool, the public pool of unconfirmed transactions that anyone on the network can inspect. A predatory bot spots Alice’s pending order, submits its own buy transaction before hers, and then places a sell transaction immediately after hers, causing her swap to execute at a significantly worse price rate. This is referred to as front‑running in decentralized finance. Front‑running happens when someone has advance knowledge of your pending transaction and executes theirs first to profit from the predictable price impact.

Peek into any mempool and you will see two main front‑running strategies at work: sandwich attacks, where a bot places orders before and after yours to skim the spread; and generalized front‑running, where it copies your pending transaction (for example, an arbitrage transaction) to capture the associated profit before you. Both tactics exploit the transparent pool of unconfirmed transactions and rely on advance knowledge of your intent. The sandwich technique squeezes your trade on both sides for profit, while generalized front‑running steals the profit your transaction was intended to secure.

What can we do against front-running?

Given the prevalence of front‑running on blockchains like Ethereum, their public mempools are often called a “dark forest” where bots prey on unconfirmed transactions. This environment has inspired a range of academic and industry proposals to address front‑running, and we will explore their respective strengths and weaknesses.

Trusted-third party ordering

Imagine Alice skips the public mempool and sends her swap directly to a single sequencer. That sequencer queues each transaction in the exact order received and executes them in turn. For Alice, this feels like breathing fresh air: her trade confirms quickly, with no additional fees or unpredictable delays. The catch is that she has handed full control over ordering to one operator, sacrificing decentralization and censorship resistance. If the sequencer chooses to delay, reorder, or block her transaction, Alice has no fallback option. To reduce this risk, some systems run the sequencer inside a trusted execution environment (TEE) providing cryptographic attestation of fair handling, but the core trade-off between efficiency and centralization remains.

Algorithmic committee ordering

Consider a model where Alice sends her transaction to a committee rather than a single sequencer. This approach, referred to as algorithmic committee ordering, has the group of validators run a consensus protocol to agree on an ordering that approximates first-come, first-served (FCFS), since network delays make agreement on exact FCFS between a distributed set of nodes impossible. By spreading sequencing responsibility across multiple nodes, it tolerates a subset of Byzantine actors and avoids a single point of failure, but it still concentrates influence among committee members and favors those with faster network connections. In some implementations, the nodes in the committee run inside a TEE, reducing how much Alice needs to trust the committee members.

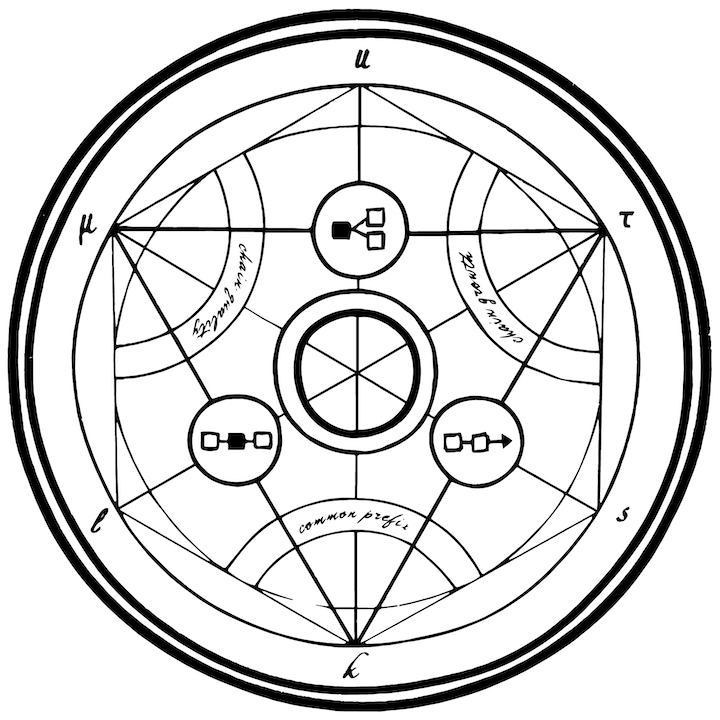

Commit and reveal

This approach, known as commit and reveal, or otherwise referred to as encrypted mempools, begins with Alice locking her swap into an encrypted envelope by publishing only the ciphertext. The network then orders these sealed commitments without knowing what’s inside. At the reveal stage, the decryption key becomes available and validators unlock each envelope to execute the underlying transaction in its reserved position. Commit and reveal protocols keep pending transactions completely hidden, giving Alice some of the strongest protection against front-running and reducing her reliance on any single actor. The trade-offs include two extra protocol phases that add latency and on-chain overhead, as well as the potential for higher transaction revert rates given the added uncertainty regarding the state they will execute on.

MEV redistribution

To turn front-runner profits into user gains, Alice can opt into MEV redistribution. Rather than just sending her swap to the public mempool, her transaction enters an auction where searchers submit bids for the right to front-run and/or back-run her transaction in a bundle. When the auction closes, Alice’s trade executes along with the winning bundle. Further, a share of the winning bid is paid directly to Alice, giving her a share of the upside that her transaction generated. In a healthy, competitive market without collusion, bids climb toward the true extractable value, ensuring Alice captures most of the upside. This model depends on a diverse ecosystem of searchers and robust auction mechanics to prevent collusion. At the same time, running the auction can add extra steps to the process, which may introduce delays for Alice’s trade.

Why is front-running still prevalent?

Now these defenses all exist, yet Alice still gets sniped. After a quiet afternoon, she checks her wallet and discovers her swap was front-run once again. Why is this happening? Most protections require users to opt in; they only shield those who actively enable them. A handful of mechanisms could protect every user by default, but the majority of those implemented only help users who know to use them. For example, Flashbots has offered users a service to submit their transactions privately 1 for multiple years, but has done little to defend the traders most at risk. If Alice never learns about these shields, she never activates them and remains prey to mempool predators.

Where do we go from here?

In the short term, we must bring every Alice up to speed and build protections into the tools she already uses. Education campaigns, i.e., tutorials, blog posts and in-app tips 2 3 4, can make all users aware of front-running risks and defenses. Meanwhile, wallet and RPC providers should bake in default safeguards for every transaction. By submitting transactions privately, for example, every swap gets a layer of protection without requiring Alice to opt in. In the long term, we need to move beyond today’s stopgap measures. Many of the solutions we’ve seen introduce unwanted centralization or impose efficiency costs. To deliver fairness, decentralization, and performance in one package, the community must continue researching new protocol designs. Only by pushing this frontier can we ensure that every Alice trades on a truly level playing field by default.