Upon entering the University College London’s Student Centre, one might stand for a few seconds to observe an odd figure. Sitting on a chair by the door is a mummy, which consists of the skeleton and wax head of UCL’s spiritual founder, Jeremy Bentham. Bentham was a man of many eccentricities, among which owning a knighted cat named “The Reverend Sir John Langbourne”, who regularly ate macaroni at his table, and maybe inventing jogging, or “circumgyration” as he called it. Perhaps more importantly though, he was the first systematic developer of the theory of utilitarianism.

Utilitarianism originated from the idea that morally appropriate behavior increases happiness (utility). As the field of economics was gradually established, this philosophical idea became an assertion about human nature - or, as another philosopher and political economist named Francis Ysidro Edgeworth blatantly put it, “every man is a pleasure machine”. In the 21st century, where the rise of computer science has enabled faster reasoning and produced new sub- and cross-disciplines, like algorithmic game theory, the heart of game theory is still rooted in this utilitarian worldview of the 19th century.1

The most classic game theoretic example is the prisoners’ dilemma. In this thought experiment, two thieves, Lilo and Stitch, have been captured by the police and are being interrogated. The police officers have some condemning evidence for both thieves, enough to put them in jail for at least 1 year. However, they also present each thief with an option: either rat on the other thief or stay silent. If both thieves stay silent, they will both serve 1 year in prison. If Lilo rats on Stitch, then Lilo walks away while Stitch gets 4 years in prison; the same holds for Stitch. However, if both Lilo and Stitch rat on each other, then the total incarceration duration is split among them, with each thief serving 2 years. Crucially, Lilo and Stitch are kept in separate cells and cannot communicate at all.

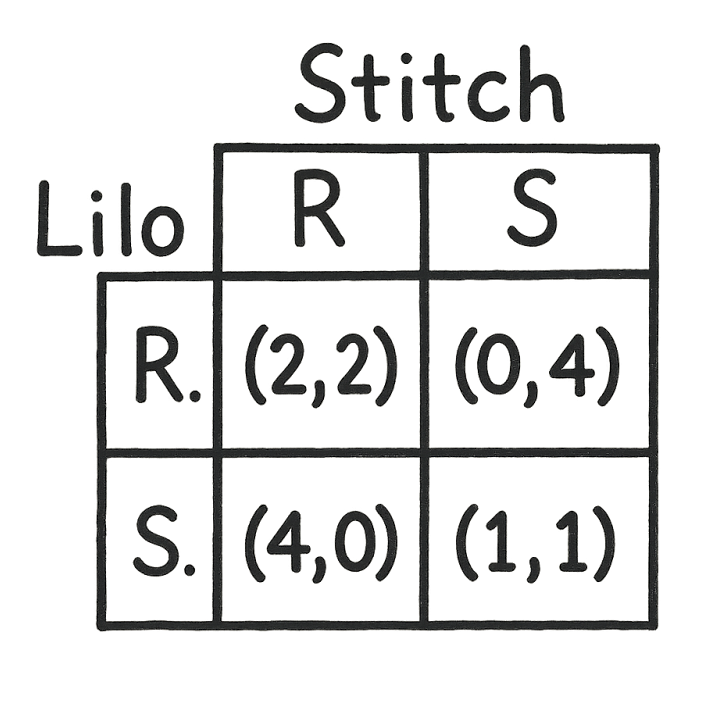

In game theory, this situation is modelled as a game of two players and two strategies. The players (Lilo and Stitch) can choose to either (i) rat (R strategy) or (ii) stay silent (S strategy). The payoffs combinations of the four strategy combinations are depicted in the following table (“payoff matrix”). Naturally, each person’s utility, that is what they want, is to minimize the amount of time that they spend in jail. Looking at the payoff matrix, one can easily deduce which strategy is optimal for each player. If Lilo stays silent then: (i) if Stitch rats on her, he gets no prison time; (ii) if Stitch stays silent, he will serve 1 year in prison. If Lilo rats on Stitch then: (i) if Stitch also rats on her, she gets 2 years in prison; (ii) if Stitch stays silent, he faces a 4-year sentence. Regardless what Lilo does, if Stitch rats on her then he will spend less time in prison than he would by staying silent. By symmetry, the exact same holds for Lilo. Therefore, for both players in this game the rational option is to rat on each other. The more interesting aspect of this game is that the R/R setting is suboptimal for the pair of them. If they both stay silent, they each serve 1 year in prison, 2 in total. By choosing to rat, they serve 4 years in total.

The conceptual simplicity and intriguing structure are what make the prisoners’ dilemma so appealing and popular. In fact, it is often cited as proof of the self-serving nature of humans, who try to do what’s best for themselves. However, proponents of such arguments often forget that in fact there is nothing natural in a person looking out only for themselves. What I called “natural” above, that each person wants to minimize their time in jail, is actually not a fact, but an assertion. In reality, jail time is one of many factors that affect a person’s decision. If Lilo and Stitch are childhood friends, betraying the person they love and admire would hurt their feelings significantly. Considering such intricate relationships between people and codifying them in clear equations is particularly difficult, if not impossible. Therefore, instead of being paralyzed by the inability to define a utility that captures all real world intricacies, researchers typically come up with a model that approximates reality and require their virtual economic androids to “act rationally”.

In blockchain research game theory plays a central role. Since Bitcoin’s inception, blockchain-based distributed ledgers have been intertwined with incentives via token rewards. These rewards are straightforward, so blockchain analyses’ typically assume that the utility of blockchain actors revolves around the amount of tokens that they receive, either as an absolute number or proportion of the overall existing tokens. This approach has produced a long list of theoretical results, both positive and negative, which often analyze the same system, typically Bitcoin, and are mathematically correct. As such, we end up in a situation where two papers show that a system like Bitcoin both is and is not secure, depending on the utility function that its participants are presumed to follow.

For example, it is known that, if participants care about maximizing their absolute rewards, they will run Bitcoin’s protocol correctly.2 At the same time, over 10 years ago Bitcoin was shown to be vulnerable to a game theoretic attack called “selfish mining”, which assumes that participants care about their relative share of rewards.3 Interestingly, given selfish mining’s simplicity and robustness, as well as the rise of Bitcoin’s popularity, the lack of widespread attempts of launching this attack4 has led scientists to devise alternative models in order to explain the observed world.5

Which begs the question, when a paper’s result contrasts with real-world observations, is this behavior really “irrational”, or is the analysis missing something? Is it possible to define a model rich enough to encompass all elements of a protocol’s implementation, in a way that accurately explains or even predicts the behavior of participants?

Albeit such philosophical questions rarely receive clear-cut answers, it seems that people are often too complicated to be modelled accurately. Invariably, inaccurate models and analyses lead to faulty, or rather inapplicable, results. What can we do about it? Are the theoretical models at fault? Possibly - oversimplifying the motives and behavior of people often leads to artificial results, based on models that bear little semblance to reality. Are people acting “irrationally”? Not necessarily - people’s motives and rationale are often misunderstood, whereas other times they may even act against their own stated wants and needs for no apparent reason.6 Is theoretical analysis inconsequential and should systems’ developers and users just ignore it? Certainly not - even if an attack has not happened yet, it doesn’t mean that it is not realistically possible, and even if a model is somewhat inaccurate, it can always serve as a stepping stone for a more detailed and accurate analysis. Therefore, game theoretic research should always be carefully taken into account when deploying, maintaining, or using a service, but should also be informed by the existence and evolution of real world systems.

Acknowledgments:

We thank Dr. Zeta Avarikioti for her valuable feedback on this post.

References

- For more on the history of economics see The Worldly Philosophers by Robert L. Heilbroner, possibly the most pleasurable economics book ever written.

- The Economics of Bitcoin Mining, or Bitcoin in the Presence of Adversaries; Joshua A. Kroll, Ian C. Davey, and Edward W. Felten; https://w.econinfosec.org/archive/weis2013/papers/KrollDaveyFeltenWEIS2013.pdf

- Majority is not Enough: Bitcoin Mining is Vulnerable; Ittay Eyal and Emin Gun Sirer; https://arxiv.org/abs/1311.0243

- For example see: ForkDec: Accurate Detection for Selfish Mining Attacks; Zhaojie Wang, Qingzhe Lv, Zhaobo Lu, Yilei Wang, and Shengjie Yue; https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/2021/5959698

- For example see: The Dynamics of a “Selfish Mining” Infested Bitcoin Network: How the Presence of Adversaries Can Alter the Profitability Framework of Bitcoin Mining; Jake A. Gober; https://dash.harvard.edu/entities/publication/0d44c68f-35c4-4415-a34c-99ebf0221344

- For example, a very interesting recent result on auction bidding shows that, in practice, people may not always follow the “correct” (truthful) strategy, even though it is rational for them to do so: A Novel Experimental Test of Truthful Bidding in Second-Price Auctions with Real Objects; Antonio Rosato and Agnieszka A. Tymula; https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/115427/1/MPRA_paper_115427.pdf